No trial provides a better basis for understanding the nature and causes of evil does than the Nuremberg trials from 1945 to 1949. Those who come to the trials expecting to find sadistic monsters are generally disappointed. What is shocking about Nuremberg is the ordinariness of the defendants: men who may be good fathers, kind to animals, even unassuming–yet who committed unspeakable crimes. Years later, reporting on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, Hannah Arendt wrote of “the banality of evil.” Like Eichmann, most Nuremberg defendants never aspired to be villains. Rather, they over-identified with an ideological cause and suffered from a lack of imagination or empathy: they couldn’t fully appreciate the human consequences of their career-motivated decisions.

Twelve sets of trials, involving over a hundred defendants and several different courts, took place in Nuremberg from 1945 to 1949. By far the most attention–not surprisingly, given the figures involved–has focused on the first Nuremberg trial of twenty-one major war criminals. Several of the eleven subsequent Nuremberg trials, however, involved conduct no less troubling–and issues at least as interesting–as the Major War Criminals Trial. For example, the trial of sixteen German judges and officials of the Reich Ministry (The Justice Trial) considered the criminal responsibility of judges who enforce immoral laws. (The Justice Trial became the inspiration for the acclaimed Hollywood movie, Judgment at Nuremberg.) Other subsequent trials, such as the Doctors Trial, which decided the fates of 23 Nazi physicians who conducted horrific medical studies, and the stomach-turning Einsatzgruppen Trial, which considered punishment for 24 members of German mobile killing units, are especially compelling because of the horrific events described by prosecution witnesses. (These three subsequent trials each receive separate coverage elsewhere in this website.)

In 1944, when eventual victory over the Axis powers seemed likely, President Franklin Roosevelt asked the War Department to devise a plan for bringing war criminals to justice. Before the War Department could come up with a plan, however, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau sent his own ideas on the subject to the President’s desk. Morgenthau’s eye-for-an-eye proposal suggested summarily shooting many prominent Nazi leaders at the time of capture and banishing others to far off corners of the world. Under the Morgenthau plan, German POWs would be forced to rebuild Europe. The Treasury Secretary’s aim was to destroy Germany’s remaining industrial base and turn Germany into a weak, agricultural country.

Secretary of War Henry Stimson saw things differently than Morgenthau. The counter-proposal Stimson endorsed, drafted primarily by Colonel Murray Bernays of the Special Projects Branch, would try responsible Nazi leaders in court. The War Department plan labeled atrocities and waging a war of aggression as war crimes. Moreover, it proposed treating the Nazi regime as a criminal conspiracy.

Roosevelt eventually chose to support the War Department’s plan. Other Allied leaders had their own ideas, however. Churchill reportedly told Stalin that he favored execution of captured Nazi leaders. Stalin answered, “In the Soviet Union, we never execute anyone without a trial.” Churchill agreed saying, “Of course, of course. We should give them a trial first.” All three leaders issued a statement in Yalta in February, 1945 favoring some sort of judicial process for captured enemy leaders.

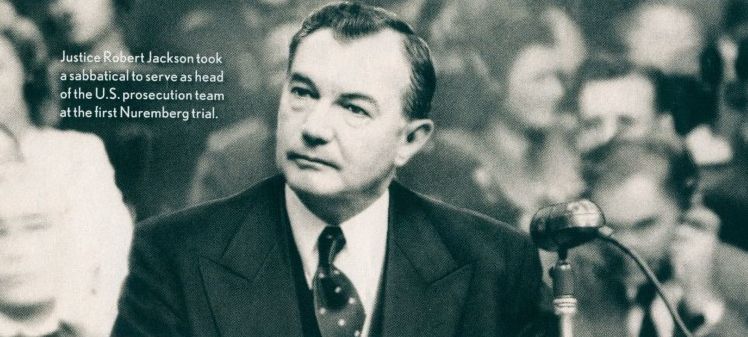

In April, 1945, two months after Yalta and two weeks after the sudden death of President Roosevelt, Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson received Samuel Rosenman at his Washington home. Rosenman asked Jackson, on behalf of President Truman, to become the chief prosecutor for the United States at a war-crimes trial to be held in Europe soon after the war ended. Truman wanted a respected figure, a man of unquestioned integrity, and a first-rate public speaker, to represent the United States. Justice Jackson, Rosenman said, was that person. Three days later, Jackson accepted. On May 2, Harry Truman formally appointed him chief prosecutor. But prosecutor of whom, and under what authority? Many questions remained unanswered.

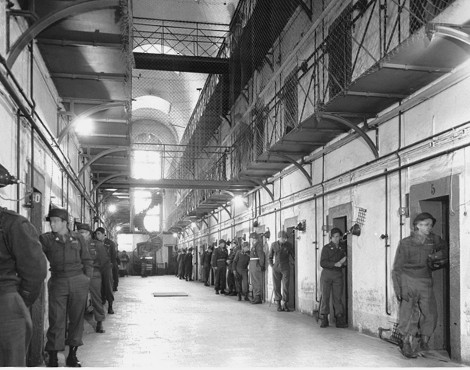

Guards stand by cells in Nuremberg’s prison housing Nazi war criminals.

Fifty Years Later: The Significance of the Nuremberg Code

The New England Journal of Medicine

In the last days of the war in Europe, several Nazi leaders escaped trial and punishment. Two days before Jackson’s appointment, in a bunker twenty feet below the Berlin sewer system, Adolf Hitler shot himself. Soon thereafter, Heinrich Himmler–perhaps the most terrifying figure in the Nazi regime–took a cyanide crystal while being examined by a British doctor and died within minutes. Also unavailable for trial were Joseph Goebbels, who shot himself in a garden, and Martin Bormann (missing).

Still, many important Axis leaders had fell into Allied hands, either through surrender or capture. Deputy Fuhrer Rudolph Hess had been held in England since 1941, when he had parachuted into the Scottish sky in a solo effort to convince British leaders to make peace with the Nazi government. Reischsmarschall Hermann Goering surrendered to Americans on May 6, 1945. He spent his first evening in captivity happily drinking and singing with American officers–officers who later were reprimanded by General Eisenhower for the special treatment they conferred. Hans Frank, “the Jew Butcher of Cracow,” received less hospitable treatment from American soldiers in Bavaria, who forced him to run through a seventy-foot line of soldiers, getting kicked and punched the whole way. Other suspected war criminals were rounded up on May 23 by British forces in Flensburg, site of the last Nazi government. The Flensburg group included Karl Doenitz (Hitler’s successor as fuhrer), Field Marshall Wilhelm Keitel, Nazi Party philosopher Alfred Rosenberg, General Alfred Jodl, and Armaments Minister Albert Speer. Eventually, twenty-two of these captured major Nazi figures would be indicted.

On June 26, Robert Jackson flew to London to meet with delegates from the other three Allied powers for a discussion of what to do with the captured Nazi leaders. Every nation had its own criminal statutes and its own views as to how the trials should proceed. Jackson devoted such considerable time to explaining why the criminal statutes relating to wars of aggression and crimes against humanity that he proposed drafting would not be ex post facto laws. Jackson told negotiators from the other nations, “What we propose is to punish acts which have been regarded as criminal since the time of Cain and have been so written in every civilized code.” The delegates also debated whether to proceed using the Anglo-American adversarial system with defense lawyers for the defendants, or whether instead to use the judge-centered inquisitive system favored by the French and Soviets.

After ten days of discussion, the shape of the proceedings to come became clearer. The trying court would be called the International Military Tribunal, and it would consist of one primary and one alternate judge from each country. The adversarial system preferred by the Americans and British would be used. The indictments against the defendants would prohibit defenses based on superior orders, as well as tu quoque (the “so-did-you” defense). Delegates were determined not to let the defendants and their German lawyers turn the trial into one that would expose questionable war conduct by Allied forces.

The plan for the trials didn’t sit well with all of Jackson’s fellow justices. Justice William O. Douglas complained that the Allies were guilty of “substituting power for principle” at Nuremberg. He argued that the laws to be applied were created after the fact “to suit the clamor of the time.” Chief Justice Harlan Stone was blunter, calling the Nuremberg trials “a fraud” and “a high-grade lynching party.” Stone added, “I don’t mind what Jackson does to the Nazis, but I hate to see the pretense that he is running a court and proceeding according to common law.”

Courtroom in the Palace of Justice being readied for trials

Jackson believed that the war crimes trials should be held in Germany. Few German cities in 1945, however, had a standing courthouse in which a major trial could be held. One of the few cities that did was Nuremberg, site of Zeppelin Field and some of Hitler’s most spectacular rallies. It was also in Nuremberg that Nazi leaders proclaimed the infamous Nuremberg Laws, stripping Jews of their property and basic rights. Jackson liked that connection. The city was 91% destroyed, but in addition to the Palace of Justice, the best hotel in town–the Grand Hotel–was miraculously spared and served as an operating base for court officers and the world press. Over the objection of the Soviets (who preferred Berlin), Allied representatives decided to conduct the trial in Nuremberg.

On August 6, the representatives signed the Charter of the International Military Tribunal, establishing the laws and procedures that would govern the Nuremberg trials. Six days later, a cargo plane carrying most of major war trial defendants landed in Nuremberg. Allied military personnel loaded the prisoners into ambulances and took them to a secure cell block of the Palace of Justice, where they spent the next fourteen months.

Judges for the IMT met for the first time on October 13. The American judge was Francis Biddle, who was appointed to the job by Harry Truman–perhaps out of a feeling of guilt after the President dismissed him as Attorney General. Robert Jackson pressured Biddle, who desperately wanted the position of chief judge, to support instead the British judge, Sir Geoffrey Lawrence. Jackson thought the selection of a British as president of the IMT would ease criticism that the Americans were playing too large a role in the trials. Votes from the Americans, British, and French elected Lawrence chief judge.

With a November 20 opening trial date approaching, Nuremberg began to fill with visitors. A prosecutorial staff of over 600 Americans plus additional hundreds from the other three powers assembled and began interviewing potential witnesses and identifying documents from among the 100,000 captured for the prosecution case. German lawyers, some of whom were themselves Nazis, arrived to interview their clients and began trial preparation. Members of the world press moved into the Grand Hotel and whatever other quarters they could find and began writing background features on the upcoming trial. Nearly a thousand workers rushed to complete restoration of the Palace of Justice.

THE TRIAL

On the opening day of the trial, the twenty-one indicted war trial defendants took their seats in the dock at the rear of the sage green draped and dark paneled room. Behind them stood six American sentries with their backs against the wall. At 10 a.m., the marshal shouted, “Attention! All rise. The tribunal will now enter.” The judges from the four countries walked through a door and took their seats at the bench. Sir Geoffrey Lawrence rapped his gavel. “This trial, which is now to begin,” said Lawrence, “is unique in the annals of jurisprudence.” The Major War Figures Trial was underway in Nuremberg.

Indicted defendant in the Major War Criminals Trial

The trial began with the reading of the indictments. The indictments concerned four counts. All defendants were indicted on at least two of the counts; several were indicted on all four counts. Count One, “conspiracy to wage aggressive war,” addressed crimes committed before the war began. Count Two, “waging an aggressive war (or “crimes against peace”), addressed the undertaking of war in violation of international treaties and assurances. Count Three, “war crimes,” addressed more traditional violations of the laws of war such as the killing or mistreatment of prisoners of war and the use of outlawed weapons. Count Four, “crimes against humanity,” addressed crimes committed against Jews, ethnic minorities, the physically and mentally disabled, civilians in occupied countries, and other persons. The greatest of these crimes against humanity was, of course, the mass murder of Jews in concentration camps–the so-called “Final Solution.” For an entire day, defendants listened as prosecutors read a detailed list of the crimes they stood accused of committing.

THE PROSECUTION CASE

The next day Robert Jackson delivered his opening statement for the prosecution. Jackson spoke eloquently for two hours. He told the court, “The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant, and so devastating that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored because it cannot survive their being repeated. That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury, stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant tributes power has ever paid to reason.”

The prosecution case was divided into two main phases. The first phase focused on establishing the criminality of various components of the Nazi regime, while the second sought to establish the guilt of individual defendants. The first prosecutorial phase was divided into parts.

The prosecution presented the case that the Austrian invasion constituted an aggressive war, then proceeded over the course of two weeks to show the same for invasions of Czechoslovakia, Poland, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, Greece, Yugoslavia, and the Soviet Union. Prosecution proof on the counts of conspiring to wage and then waging an aggressive war consisted mainly of documentary evidence. Documentary evidence had one big disadvantage–it was boring. Hour upon hour of various letters and other communications being read into the record caused the press to flee in droves. The Allies worried that excessive reliance on documentary evidence was undermining their goal of educating the public about the horrors inflicted by the Nazi regime. Prosecutors agreed that something must be done to enliven the proceedings–so they determined to rely more heavily on real physical evidence and live witnesses.

A second part of the prosecution case concerned the Nazi’s use of slave labor and concentration camps. Evidence introduced during this part of the prosecution case brought home the true horror of the Nazi regime. For example, on December 13, 1945, U. S. prosecutor Thomas Todd introduced USA Exhibit #253: tanned human tattooed skin from concentration camp victims, preserved for Ilse Koch, the wife of the Commandant of Buchenwald, who liked to have the flesh fashioned into lampshades and other household objects for her home. Then Todd introduced USA Exhibit #254: the fist-shaped shrunken head of an executed Pole, used by Koch as a paperweight.

On December 18, the prosecution began introducing evidence to establish the criminality of the Nazi party leadership, the Reich Cabinet, the SS, the Gestapo, the SD, the SA, and the German High Command. Some of the evidence brought cries and gasps from spectators. A British prosecutor, seeking to establish the criminality of the SS, read an affidavit from Dr. Sigmund Rasher, a professor of medicine who performed experiments on inmates at Dashau concentration camp. The affidavit described an experiment conducted to determine what method to use to save German fliers pulled out of freezing North Sea waters. Rasher ordered inmates stripped naked and then thrown into tanks of freezing water. Chunks of ice were added, as workers repeatedly thrust thermometers into the rectums of unconscious inmates to see if they were sufficiently chilled. Then the inmates were pulled out of the tanks to see which of four methods of warming might work best. Experimenters dropped most inmates into either tanks of hot water, warm water, or tepid water. One quarter of the inmates were placed next to the bodies of naked female inmates. (Rapid warming with hot water was determined to be most effective.) Rasher stated in his affidavit that most of the inmates used in the experiment went into convulsions and died.

In January, a series of concentration camp victims testified about their experiences. Marie Claude Vallant-Couturier, a 33-year-old French woman, provided particularly powerful testimony about what she saw at Auschwitz in 1942. Vallant-Couturier described how a Nazi orchestra played happy tunes as soldiers separated those destined for slave labor from those that would be gassed. She told of a night she was “awakened by horrible cries. The next day we learned that the Nazis had run out of gas and the children had been hurled into the furnaces alive.”

On February 18, 1946, Soviet prosecutors introduced a film entitled Documentary Evidence of the German Fascist Invaders. The film, which consisted mostly of captured German footage, showed Nazi atrocities accompanied by Russian narration. In one scene a boy is shown being shot because he refused to give his pet dove to an SS man. In another scene, naked women are forced into a ditch, then made to lie down as German soldiers–smiling for the camera–shoot them.

The prosecution rested on March 6. After the thirty-three witnesses and hundreds of exhibits that had been produced, no one could deny that crimes against humanity had been committed in Europe.

The major war trial defendants listen to testimony

THE DEFENSE CASE

Hermann Goering took his seat in the witness chair wearing a gray uniform and yellow boots. His defense attorney, Otto Stahmer, asked whether the Nazi party had come to power through legal means. In a long answer delivered without notes, Goering gave his account of the Nazi rise to power. He told the court, “Once we came to power, we were determined to hold on to it under all circumstances.” Goering was unrepentant. He evaded no questions; offered no apologies. He testified that the concentration camps were necessary to preserve order: “It was a question of removing danger.” The leadership principle, which concentrated all power in the Fuhrer, was “the same principle on which the Catholic church and the government of the USSR are both based.” Commenting on Goering’s performance in the witness box, Janet Flanner of the New Yorker described Goering as “a brain without a conscience.”

Goering enters the defendants’ dock

The courtroom was crowded on March 18, when Robert Jackson began his long awaited cross-examination of Goering. Goering at first managed to deflect most of Jackson’s intended blows, often providing lengthy answers that buttressed points he made on his direct examination, such as the fact that he had opposed plans to invade Russia. Only by the third day of cross-examination did Jackson begin scoring points. He asked Goering whether he signed a series of decrees depriving Jews of the right to own businesses, ordering the surrender of their gold and jewelry to the government, barring claims for compensation for damage to their property caused by the government. Goering, trembling at times, was given little opportunity to do more than admit the truth of Jackson’s assertions. After describing the awful events of Kristallnacht, November 9, 1938, when 815 Jewish shops were destroyed and 20,000 Jews arrested, Jackson asked Goering whether words he was quoted as saying at a meeting of German insurance officials (concerned about the loss of non-Jewish property on consignment at the Jewish shops) was accurate: “I demand that German Jewry shall for their abominable crimes make a contribution of a billion marks….I would not like to be a Jew in Germany.” Goering admitted that the quote was accurate. When Jackson finally ended his four-day cross-examination, reviews came in mixed. Most observers believed Goering had shown himself to be a brilliant villain.

Over the course of the next four months, lawyers for each of the defendants presented their evidence. In most cases, the defendants themselves took the stand, trying to put their actions in as positive of a light as possible. Many of the defendants claimed to know nothing of the existence of concentration camps or midnight killings. Typical was Joachim von Ribbentrop. Asked on cross-examination, “Are you saying that you did not know that concentration camps were being carried out on an enormous scale?”, Ribbentrop replied, “I knew nothing about that.” Prosecutor Maxwell-Fyfe then displayed a map showing a number of concentration camps located near several of Ribbentrop’s many homes. Other defendants used their testimony to emphasize that they were merely following orders–although the IMT disallowed defense of superior orders, the issue was raised anyway in the hope that it might affect sentencing.

Sometimes defense evidence actually strengthened the prosecution’s case. Such was the case on April 15, when the attorney for Gestapo and SD Chief Ernst Kaltenbrunner called Colonel Rudolf Hoess to the stand. Hoess was the commandant of Auschwitz. Why he was called as a defense witness remains a mystery. Speculation is that it was thought his testimony, revealing his very large role in the gassing of thousands of inmates, might make Kaltenbrunner’s guilt seem small in comparison. Hoess’s matter-of-fact account of mass executions using Zyklon B gas–sometimes 10,000 inmates killed in a single day–left many in the courtroom stunned.

Albert Speer

A few of the defendants confessed their mistakes and offered apologies for their actions. Wilhelm Keitel regretted “orders given for the conduct of war in the East, which were contrary to accepted usages of war.” Hans Frank, Nazi Governor of Poland, answered “Yes” when asked whether he “ever participated in the annihilation of the Jews.” “My conscience does not allow me simply to throw the responsibility simply on minor people….A thousand years will pass and still Germany’s guilt will not have been erased.” Albert Speer, Minister of Armaments, was the most willing of all defendants to accept blame. “This war has brought an inconceivable catastrophe,” Speer testified, “Therefore, it is my unquestionable duty to assume my share of responsibility for the disaster of the German people.” After Speer finished his testimony The London Daily Telegraph described it as “a tremendous indictment which might well stand for the German people and posterity as the most important and dramatic event of the trial.”

Hans Frank testifies

As June ended, the last of the twenty-one defendants, Hans Fritzsche, completed his testimony. The defense rested.

SUMMATIONS AND VERDICT

Defense summations had been underway for two days when they were interrupted on July 6 for the trial in absentia of Martin Bormann, the notorious Jew-hater who served as Hitler’s private secretary and who transmitted his most barbaric orders. Rumors abounded that Bormann might be in Spain, Argentina, or some German hideaway, but the Allies had been unsuccessful in tracking him down. Bormann’s lawyer, Friedrich Bergold, offered an unusual defense, but perhaps the only one open to him: he argued that his client was dead. (Bormann’s remains were finally identified in Berlin in 1972.)

After the Bormann case concluded, summations for the defense resumed. Robert Jackson stopped coming to court, using the time instead to draft his own closing argument–one that he hoped would make a strong moral statement to the world. Defense summations continued for over two more weeks, finally concluding with the closing argument for Rudolf Hess, on July 25.

Justice Robert Jackson (American Bar Journal)

The courtroom in the Palace of Justice, which had largely emptied for the defense summations, was full again on July 26, 1946, for the much anticipated closing argument of Robert Jackson. Jackson took shots at each of the defendants in turn. His strongest attacks were reserved for Goering. In the dock, Goering–with perverse pride–kept a count of references to him. Speer and the other repentant defendants got off the lightest. Jackson concluded his summation with a passage from Shakespeare:

“[T]hese defendants now ask this Tribunal to say that they are not guilty of planning, executing, or conspiring to commit this long list of crimes and wrongs. They stand before the record of this Trial as bloodstained Gloucester stood by the body of his slain king. He begged of the widow, as they beg of you: ‘Say I slew them not.’ And the Queen replied, ‘Then say they were not slain. But dead they are…’ If you were to say of these men that they are not guilty, it would be as true to say that there has been no war, there are no slain, there has been no crime.”

The last stage of the long trial was a defense of the Nazi organizations, followed by final statements by each of the defendants. On Saturday, August 31, the first of the indicted defendants, Hermann Goering, moved to the middle of the dock where a guard held before him a microphone suspended from a pole. Goering told the court that the trial had been nothing more than an exercise of power by the victors of a war: justice, he said, had nothing to do with it. Rudolf Hess offered an odd final statement, filled with references to visitors with “strange” and “glassy” eyes. He ended by saying it had been his “pleasure” to work “under the greatest son which my people produced in its thousand-year history.” Some defendants offered apologies. Some wept. Albert Speer offered a warning. He spoke of the even more destructive weapons now being produced and the need to eliminate war once and for all. “This trial must contribute to the prevention of wars in the future,” Speer said. “May God protect Germany and the culture of the West.”

On Tuesday, October 1, the twenty-one defendants filed into the courtroom for the last time to receive the verdicts of the tribunal. Sir Geoffrey Lawrence told the defendants that they must remain seated while he announced the verdicts. He began with Goering: “The defendant, Hermann Goering, was the moving force for aggressive war, second only to Adolf Hitler….He directed Himmler and Heydrich to ‘bring about a complete solution of the Jewish question.'” There was no mitigating evidence. Guilty on all four counts. Lawrence continued with the verdicts. In all, eighteen defendants were convicted on one or more count, three (Schact, Von Papen, and Fritzsche) were found not guilty. The three acquitted defendants did not have long to enjoy their victory. In a press room surrounded by reporters, they received from a German policeman warrants for their arrests. They were to next be tried in German courts for alleged violations of German law.

Sentences were announced in the afternoon for the convicted defendants. Again, Lawrence began with Goering: “The International Military Tribunal sentences you to death by hanging.” Goering, without expression, turned and left the courtroom. Ten other defendants (Ribbentrop, Keitel, Rosenberg, Frank, Frick, Kaltenbrunner, Streicher, Sauckel, Jodl, and Seyss-Inquart) were also told they would die on a rope. Life sentences were handed down to Hess, Funk, and Raeder. Von Schirach and Speer received 20-year sentences, Von Neurath a 15-year sentence, while Doenitz got a 10-year sentence. The trial had lasted 315 days.

Over the next two weeks, the condemned men met for the last times with family members and talked with their lawyers about their last-ditch appeal to the Allied Control Council, which had the power to reduce or commute sentences. On October 9, the Allied Control Council, composed of one member from each of the four occupying powers, met in London to discuss appeals from the IMT. After over three hours of debate, the ACC voted to reject all appeals. Four days later, the prisoners were informed that there last thin hope had disappeared.

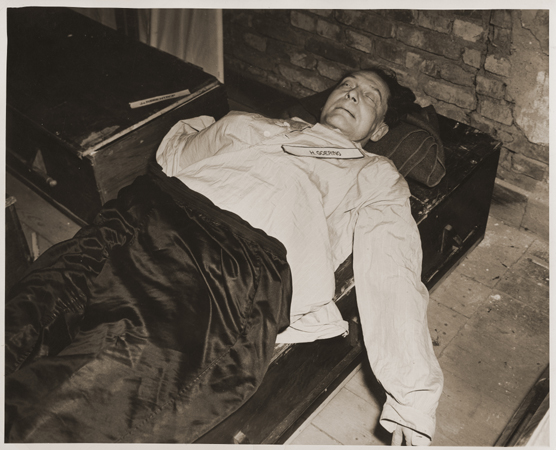

On October 15, the day before the scheduled executions, Goering sat at the small desk in his prison cell and wrote a note:

“To the Allied Control Council:

I would have had no objection to being shot. However, I will not facilitate execution of Germany’s Reichsmarschall by hanging! For the sake of Germany, I cannot permit this. Moreover, I feel no moral obligation to submit to my enemies’ punishment. For this reason, I have chosen to die like the great Hannibal.”

Then Goering removed a smuggled cyanide pill and put it in his mouth. At 10:44 p.m., a guard noticed saw Goering bring his arm to his face and then began making choking sounds. A doctor was called. He arrived just in time to see Goering take his last breath.

Body of Goering after he committed suicide with a smuggled cyanide pill

A few hours later, at 1:11 a.m. on October 16, Joachim von Ribbentrop walked to the gallows constructed in the gymnasium of the Palace of Justice. Asked if he had any last words, he said, “I wish peace to the world.” A black hood was pulled down across his head and the noose was slipped around his neck. A trapdoor opened. Two minutes later, the next in line, Field Marshal Keitel, stepped up the gallows stairs. By 2:45 a.m., it was all over.

AFTERMATH

Trials of Germans continued in Nuremberg for over two more years. The International Military Tribunal was done with its work, however. All judges for the subsequent Nuremberg trials would be drawn from the American judiciary. The Nuremberg trials continue to generate discussion. Questions are raised both about the legitimacy of the tribunals and the appropriateness of individual verdicts they reached.

More important, perhaps, is the question of whether Nuremberg mattered. No one could deny that the trials served to provide thorough documentation of Nazi crimes. In over half a century, the images and testimony that came out of Nuremberg have not lost their capacity to shock. The trials also helped expose many of the defendants for the criminals they were, thus denying them a martyrdom in the eyes of the German public that they might otherwise have achieved. There are no statues commemorating Nazi war heroes; Germany became a democracy with an educational system that teaches the truth about the country’s dark past.

The Nuremberg trials did not, however, fulfill the grandest dreams of those who advocated them. They have not succeeded in ending wars of aggression. They have not put an end to genocide. Crimes against humanity are with us still.